hanabi

So this blog post is the start of a month-long experiment. In honour of NaNoWriMo, I've decided to post here daily during Nov 2023. Short is OK. Semi-coherent is OK. Missing a day and catching up the next is OK. The goal is that, by 11:59pm on Nov 30, 2023, I'd like to have written and published 30 blog posts this month.

Here goes. Wish me luck!

This post is about one of my favourite games: Hanabi. It's not the best-designed game I've played, nor is it the most fun. It has no real narrative.

So why do I like it so much? More than any game I've played, it does a masterful job of teaching some valuable life lessons:

- you can't communicate without a shared language;

- half of working together is seeing the problem through the eyes of others;

- maybe that worry or fear you're holding onto just isn't important.

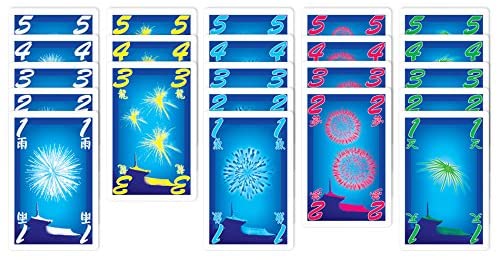

If I had to describe Hanabi in three words? Reverse Group Solitaire. Like Solitaire, you're trying to complete card sequences in each suit. Hanabi suits are colours, and there are 5 of them:

Unlike Solitaire, you play Hanabi in a group of 3-5 (instead of 1), and you can't see your own cards. Instead, you hold your hand in reverse, showing it outwards to other players:

As a team, you start with 8 clues, 3 strikes, and no cards in play. Players take turns around the table, each taking one of three actions:

- help: you use a clue to tell another player something about their hand. (There are more specific rules here, but they don't matter here.)

- play: you play a card. If it starts or continues a sequence, it stays in play. If not, it leaves play and you use a strike. You then draw a card.

- discard: you discard a card, and gain a clue. You then draw a card.

At the end of the game, your team's score is the number of cards in play. There's no winning or losing, just doing better or worse than you expected. (Maybe that's another good life lesson.)

New players at Hanabi often struggle with interpreting clues. Someone just told me this card is blue. Should I play it? Clues are limited, so players quickly learn to use them well: if I give you a clue, I want you to do something with that clue - but by the rules, I can't tell you what that something is! Maybe the blue card is the next card in a sequence, and I want you to play it. Maybe we've already finished the blue sequence, so you can safely discard it. Maybe it's a card you should hold on to.

As you play, the group evolves conventions. Early in the game, if I tell you it's a 1, play it. This builds a shared language around the low-bandwidth communication channel of Hanabi clues. The shared language leads to trust: you told me it's a 1, it's early in the game, I trust you in playing this card.

Giving clues presents its own challenges. Here you have to decide: who do I give the clue to, and what do I tell them? This leads to other questions. Does the next player have something to do? What does the player across from me know about their cards? You have to see the game through the eyes of your fellow players, and figure out how best to help each other.

Deep in these mind games, you'll start to learn about your own cards as well. There are 10 4s in the game, 2 of each colour. I can see we've played 3 and discarded 2, plus the player across from me has 2 more and knows where they are. But they haven't played them. Maybe I don't have any 4s, so they don't have enough information to safely play or discard those 4s? And so on. You find yourself reasoning through the actions and thoughts of others.

And there's the last bit: discarding cards. New players hate discarding cards. It feels so risky, so final. What if I screw up the game by discarding this card? What will others think? But of course you can give each other clues. And maybe you've been around the table twice, and no one's given you a clue. Maybe your cards just aren't that important, and you need to let them go. The game encourages you to do this: you'll earn the group a clue, and you draw a new card - maybe that's the card you've been looking for!

You have to take risks to open up opportunities. You have to let go sometimes, to accept that your worries and fears often just don't matter. You can make mistakes, and people will forgive you.

And all this is why I love Hanabi. For such a simple game, it teaches so much of value, and not in the heavy-handed edutainment way: it's all emergent from the rules and gameplay. It's also easy to learn, quick to play, and kind of silly in a way I think all adults should experience once in a while.